The internet is a cool place, is it not? We now have access to information on a scale not dreamed of by our parents; our grandparents didn’t even know a lot of this information even existed. You can find countless places to pursue any of your interests. Some of the material is provided by subscription, and it’s up to you, of course, as to whether the material is worth the price of admission. But a vast amount of good stuff is available at no cost to the reader. Notice, I didn’t say at no cost. I said at no cost to the reader. If you will go back to my post on how the internet works, you can easily see that nothing is “free,” everything has a cost. The only question to answer here is who pays the cost.

Website files are stored, or hosted, on a server. That server is a piece of hardware that cost a lot of money. It is run with an operating system that cost money. It uses electricity that costs money. It sits in some building somewhere at some cost of money. As a result of all those server costs, the owner of that server must charge money to the people who want their websites hosted there. There are other costs as well: the cost to register the name of the website, and sometimes other enhancements to the website. So by the time you pay your first visit to any website, even the most simple one, quite a bit of money has been expended.

On some websites you will see advertisements. I have a couple that show up here. I have a pretty strong filter on my ad placement agreement that keeps certain types of ads from showing up. The ads on my site are safe for work, and if they aren’t, I want to know about it quickly. My ads rotate, you probably won’t see the same ad twice on my site. But some sites have specific sponsors. This ad placement can help defray the site costs.

Some advertisers place “cookies” (very small files that help your computer identify itself to the website later) on the machines of site visitors to figure out where all a visitor goes. There is a lot of useful information to be gathered from this practice, and it allows an advertiser to better understand how to tailor the campaign if the advertiser knows more about how a website visitor behaves at different types of websites. This type of cookie is known as a “tracking cookie.” There are also cookies that store user information so that when you log into a website it remembers who you are.

As useful as tracking cookies are to the advertisers, it has gotten kind of difficult to know where the good/bad line is. How much is too much for someone else to know about you, that you didn’t openly tell them? Does the advertiser of a fabric softener really need to know where you visit to find out how to pluck a duck? More importantly, if the advertiser of a fabric softener isn’t really the one putting his cookie on your machine, do you have any way of knowing that? We’re not usually so concerned about the pages we actually visit putting a cookie on our machine, in this case, as we are about “pass-through” cookie placement, or what we call “third party cookies,” that is, cookies that aren’t put there by the first party, YOU, or the second party, the page you’re intentionally visiting.

Enter “Do Not Track.” Efforts began as early as 2007, but they were primarily to be implemented manually, and as the internet has grown exponentially since its inception, that was not sustainable even at that point. Mozilla was the first to come up with a prototype across-the-board application for its Firefox browser, and Internet Explorer, Safari, Opera, and Chrome were right up behind Mozilla. It was Microsoft, however, that ruffled serious feathers with advertisers by turning it on by default in IE 10. There were even a couple of months when Apache web servers were programmed to ignore IE’s Do Not Track instruction. A couple of grownups playing “So There!”

Do Not Track is now available for all browsers. Regardless of which one you use, you can tell websites you don’t want third party cookies. I’ll show you how to do it for Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, and Opera, and I’ll address all three platforms. Note: Windows and Linux systems both use the Tools menu on the menu bar to find these settings, while Mac computers use the Preferences menu on the menu bar.

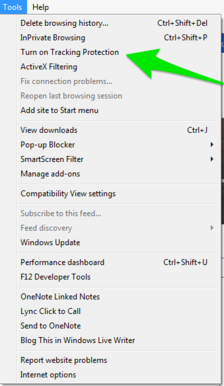

So for Internet Explorer, the latest version goes like this:

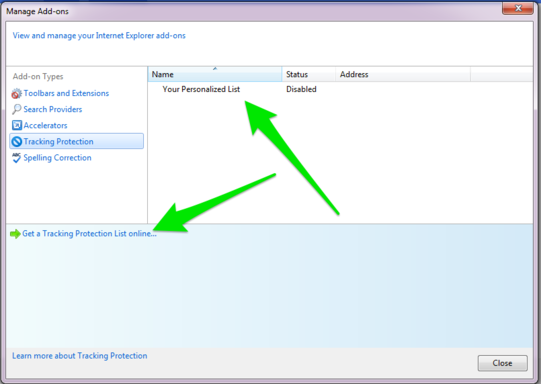

and then you see this:

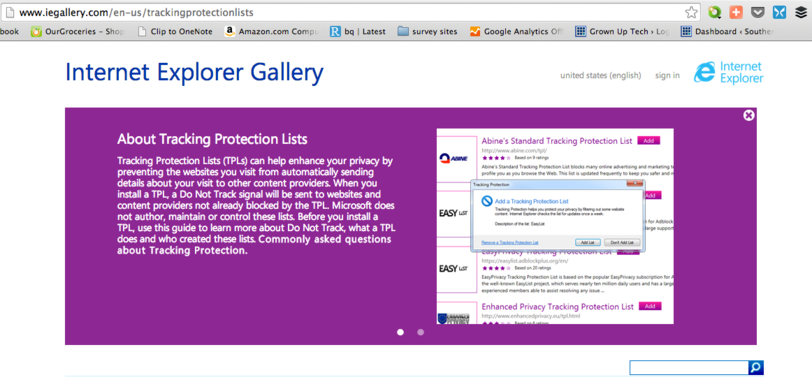

When you select “Get a Tracking Protection List online, it takes you here:

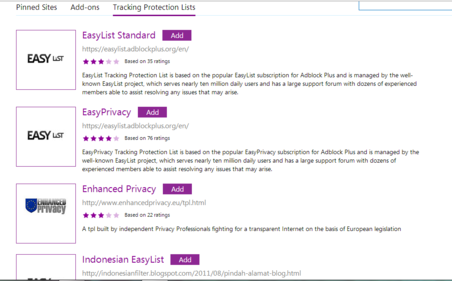

If I get any requests on how to create a tracking protection list, I’ll dig into it. But I doubt it’s necessary, because there are quite a few comprehensive lists already available:

Select one, click Add, and you’re done

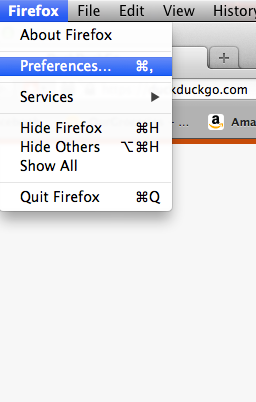

Here’s how to do the same thing for Firefox:

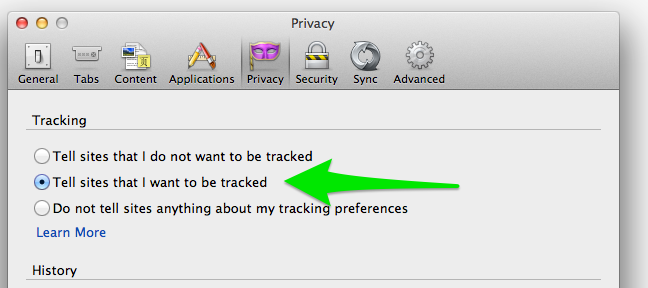

1. Open the Preferences menu and click Privacy.

2. Check the box for Tell web sites I do not want to be tracked.

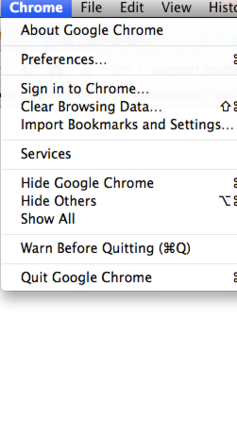

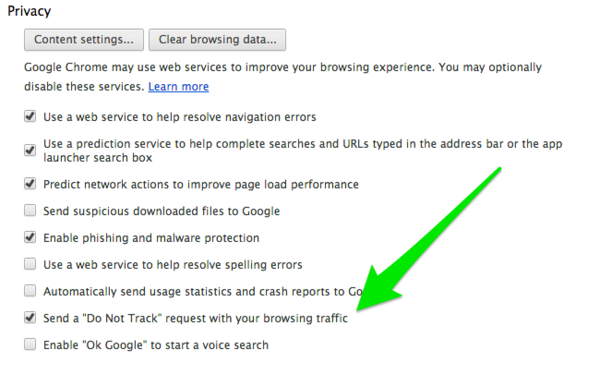

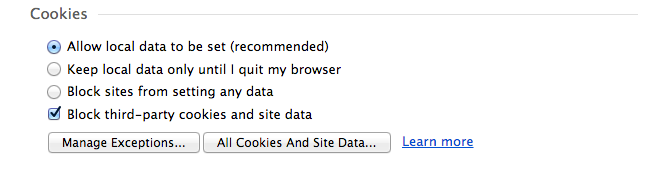

For Chrome, click on the Chrome menu, and select Preferences:

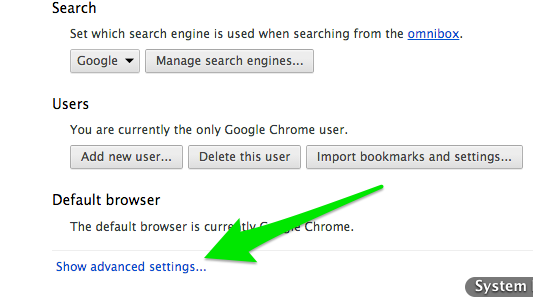

In Preferences, select Show Advanced Settings…

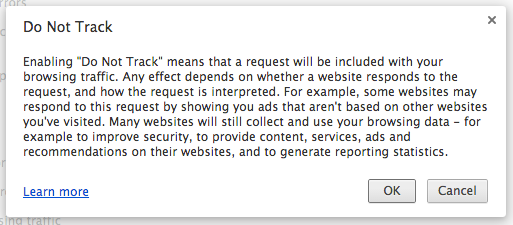

You’ll see this:

Select OK, then check the box indicated by the arrow shown below:

Then just close all the windows back to the front page.

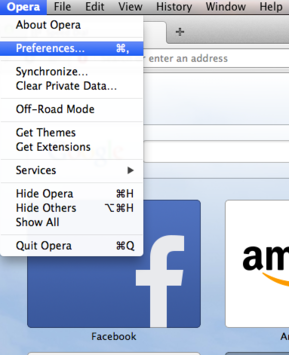

And, finally, the Opera browser:

The Opera Menu, select Preferences:

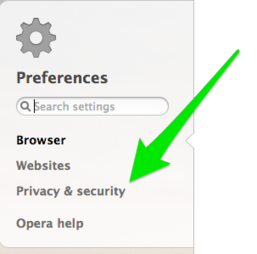

Select Privacy & security:

Mirror your settings to match these:

Then “OK” or “close” back out to the front page.

You won’t always be able to decide who knows what about you. But these steps will at least give you a little more control than you had before.

Any questions?